Reflexive Anthropology on Display: Franz Boas, George Hunt, and the Co-Production of Ethnographic Knowledge

Review By Christopher T. Green

March 21, 2019

BC Studies no. 201 Spring 2019 | p. 131-139

A portion of an 1897 letter from Franz Boas to Kwagu’ł Chiefs, reproduced in English and Kwak’wala, opens The Story Box: Franz Boas, George Hunt and the Making of Anthropology, an exhibition on view at the Bard Graduate Center Gallery, New York. “It is good that you should have a box in which your laws and stories are kept,” Boas writes. “My friend, George Hunt, will show you a box in which some of your stories will be kept. It is a book I have written on what I saw and heard when I was with you two years ago. It is a good book, for in it are your laws and your stories. Now they will not be forgotten.” The book he is referring to is The Social Organization and the Secret Societies of the Kwakiutl Indians (1897), Boas’s first monograph on Northwest Coast Indigenous culture. Frequently acknowledged as one of the most influential texts in the history of anthropology, Social Organization is among the first ethnographies based on first-person fieldwork. Our understanding of its making, however, is far from complete, as Story Box aims to demonstrate.The exhibition, like Boas, takes up the metaphor of the book-as-container – of knowledge, properties, and treasures – to explore the histories and legacies of Boas’s monumental volume and the complexities of its production.

Curated by Aaron Glass, associate professor at the Bard Graduate Center, in collaboration with the U’mista Cultural Centre (Alert Bay, BC), the exhibition brings together a wealth of archival documents, Indigenous belongings and material culture, and various forms of multimedia and reproductions to make visible the co-production of anthropological knowledge, particularly as it occurred between Boas and his aforementioned friend and essential collaborator, George Hunt. Emerging out of a larger project to produce a Critical Edition of the 1897 book, Story Box puts the secrets of ethnography on display, opting for a transparency of the anthropological process and a reversal of its hierarchies. By uncovering the layers of dispersed archives that constituted the production of Social Organization, the exhibition and larger project pursue the reconnection and reactivation of the culture knowledge that fills the gildas, or “box of treasures,” of the specific Kwakwaka’wakw families and communities with whom Hunt and Boas worked and from whom they learned.

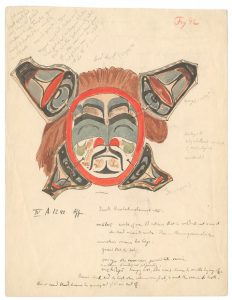

Two 1893 photographs of Boas and Hunt, flanking a group photo of Boas and the Hunt family, taken in Fort Rupert in 1894, open the central section. A major takeaway of the exhibition and the broader project is the restoration of symmetry and co-authorship between Boas and Hunt in the production of Social Organization. Hunt was more than the consultant and informant he has typically been positioned as; not only did he assist in the collecting, documenting, and transcription of stories, songs, and objects, but he drafted whole sections of the book. Judith Berman, a co-director with Glass of the Critical Edition project whose past writings have extensively investigated the nature of Hunt’s background and collaborations with Boas, speculates that Hunt’s notes and drafts make up about a third of Social Organization. A central display case, “The Making (and Remaking) of the 1897 Book,” presents such co-authorship through original fieldnotes, correspondences, archival drawings, and manuscripts to tell the missing story of the collaborative making of the book – and anthropology. One of Boas’s 1886 field notebooks from his early visits to ‘Yalis (Alert Bay) and Xwamdasbe’ (Newitti, Hope Island), filled with hastily drawn regalia, face-painting designs, and scrawled shorthand, is shown alongside watercolour paintings (1887–94) of a Kwakwaka’wakw Hamshamtses Dance transformation mask, collected by Johan Adrian Jacobsen for the Ethnologisches Museum in Berlin. Boas and Hunt showed such paintings to community members in order to solicit information on identification and associated songs and property relations, at times writing notes directly on the paintings. Such field notes informed the book and its figure captions, as included copies and reproductions of relevant pages demonstrate.

Decades after the initial publication of Social Organization, Hunt wrote to Boas in 1920 regarding its inaccuracies: “Now about the book with the many illustrations. There are so many mistakes in the names of the masks and dishes that I think should be put to rights before one of us die.” This quote is blown up on the gallery wall, and the original letter in which it appears is displayed alongside Boas’s own letter and emphatic reply: “I am very anxious that the mistakes which are in the book with the many illustrations should be corrected, and I should be very glad if you would go through it and write out the corrections.” Stunningly, the exhibition features Hunt’s personal copy of Social Organization, in which he had begun to make marginal annotations to correct the “many mistakes.” By the time of Hunt’s death in 1933, he had sent more than six hundred pages of corrections from his systematic revision to Boas. Several of the hundreds of pages of such notes and corrected manuscripts by Hunt from the 1920s to the 1930s round out the display, the central archive by which the exhibition and larger Critical Edition project bring Hunt’s emendations to bear on the 1897 book, now better understood as incomplete.

The exhibition features a number of nineteenth-century belongings, primarily masks, which are featured in the 1897 book, displayed with labels that reproduce Boas’s corresponding entries as well as Hunt’s later notes. Hunt’s emendations offer a wealth of new information and serve as correctives to Boas’s typological approach, which served to separate masks, songs, and dances from their social, genealogical, and ceremonial structures and connections. An example is a series of the lion-like masks that Boas identified as Nułamał (Fool) masks, but which Hunt argued depict Sepa’xais (Shining Down Sun Beam), a sky dweller associated with the villages of Quatsino Sound. Boas’s own reading of masks and crests relied on formal typologies (in this case, leonine features and a twisted rim motif) that divorced aesthetics from the lived politics of the hereditary relationships, downplaying the notion of masks as cultural property with associated lineages of ownership. Hunt’s notes demonstrate how similar-looking objects can have distinct meanings, names, and stories. His insights are essential for retracing the genealogical connections separated by Boas’s typology, and the reconnection of hereditary material to present-day families is a key goal for the Kwakwaka’wakw community and the larger project.

Kwakwaka’wakwartist Corrine Hunt describes this reconnection as not necessarily a rediscovery, as much of the knowledge was maintained, but rather as “a kind of reinforcement of the things we know and the knowledge that has been shared by different people in various villages.”Hunt, a member of the Critical Edition project team and descendant of George Hunt, contributed graphic and conceptual designsfor the exhibition. A series of paper sheets hanging from the ceiling of the gallery seem to rise up from a bentwood box-like display case that holds a first edition of Boas’s book. Featuring formline motifs by the artist, she describes the pages as representations of the dynamism of the stories that come out of this box. “I see it as a book that has wings,” Hunt notes in a printed conversation with Glass, and these floating stories are available again in the universe for her community to grab.

Story Box brings renewed attention to the historical conditions under which Social Organization was written. Not only was the potlatch banned the entire time during which Boas worked with the Kwakwaka’wakw, but the exhibition emphasizes the extent to which the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition was a major site of fieldwork for Boas and Hunt that could avoid such restrictions. About twenty Kwakwaka’wakw travelled to Chicago, including Hunt’s own family and extended relations, and performed songs and dances otherwise illegal in Canada, dutifully recorded and transcribed by Boas and Hunt. The second section of the exhibition uses multimedia displays to insightfully demonstrate the likewise multimedial nature of the 1897 ethnography, which featured not only texts and object illustrations but also photographs and musical scores. A ceremonial Sisiuł belt, reproduced in the 1897 book and pictured being worn at the fair by a man named Gwayułalas, is displayed alongside a wax cylinder of the kind with which Boas recorded Kwakwaka’wakw songs at the 1893 fair. A touchscreen display plays several of those recordings, along with a contemporary 1998 performance, and illustrates each song with Boas’s accompanying field notes and 1897 book entry.

Photos taken at the World’s Fair were altered for the book, whitewashed to remove traces of the cosmopolitan setting from the documentation and to make the knowledge seem more authentic. Another touchscreen display in Story Box features a virtual collection of photos used for Boas’s research and publications, particularly from his 1894 fieldwork in Fort Rupert. A before and after feature allows the viewer to swipe between the original photos and the plates modified for the book, an effective demonstration of the constructed nature of many such illustrations. Some plates are shown to be composite scenes painted from multiple (often unrelated) photo sources. The display succinctly pulls the curtain back on the common artifice of ethnography, and while the constructed nature of certain aspects of the discipline and its photographic documentation has been well rehearsed, the implications have yet to be fully digested. To prove this point the second gallery closes with a consideration of the impact of Boas and Hunt’s research on museums’ displays over time. Black-and-white images of Boas, posing for photographs on which to base his well-known Hamat’sa life group, are projected next to a wall-sized photo-reproduction of the diorama. Didactic material breaks down the diorama’s elements and its making, and Boas’s ghostly form seems to haunt the legacy of the many institutions that reproduced his displays, as demonstrated by a section that is aptly titled “Afterlives in the Museum.”

While some visitors may be disappointed by the relatively small number of objects on display and heavy reliance on photo reproductions, the final section of the exhibition demonstrates how the interweaving of commercial and community reproductions and replicas is in fact a major legacy of Social Organization. A killer whale mask carved in 2018–19 by Corrine Hunt and David Mungo Knox (Kwakwaka’wakw) is based on a transformation mask collected by Jacobsen for Berlin and illustrated in the 1897 book. Hunt’s notes on the mask show that it had once belonged to his first wife, Lucy Homiskanis (T’łaliłi’lakw), allowing his descendant to reactivate the dormant mask and its hereditary privileges. The Kwakwaka’wakw carver Wayne Alfred is likewise working with young apprentices in Alert Bay on a set of raven rattles based on one collected and reproduced by Boas. The new rattle will not be displayed until it is completed, however. Its empty display case is nonetheless a useful reminder that the value of Indigenous belongings does not always lie in the physical instantiation but, rather, in the knowledge or right that it embodies. In the case of Alfred’s rattle, the revival of the rattle’s form and use, recovered through Hunt’s revisions, are one legacy of the mediated images reproduced in the 1897 book. Artist and community researcher Andy Everson (K’ómoks/Kwakwaka’wakw), a member of the Critical Edition project team, noted at the exhibition’s opening symposium that the objects are less important than the associated rights, and that the physical and visual forms are mutable and inclined to change over time. Mechanical reproductions of objects dispersed around the world, as demonstrated by maps displaying the sites of related holdings, along with the community reproductions, thus act to emphasize such knowledge over the desire for the “originals” once collected and illustrated by Boas. Theexhibition reconfigures how this knowledge has been produced, shared, repatriated, and revitalized by current Kwakwaka’wakw for their ongoing art, lives, and ceremony.

A prototype of the forthcoming 1897 Critical Edition project shown in this final section brings further transparency and anthropological reflexivity to the exhibition. The making of the making is further revealed, with a display that describes the project and previews the digital edition. Layers of Hunt’s annotations, Boas’s notes, and contemporary commentary, language, and media will be available in the final version of the edited volume, expected to be released in 2021 with the digital edition to coincide or follow shortly thereafter. As Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett noted in her keynote response to the exhibition’s symposium, this is a relational project that brings an archaeological approach to the production of ethnographic knowledge. While many recent projects have sought to consider the legacy of Boas and his writings, Story Boxis more concerned with revealing the co-production of anthropological knowledge and its continued legacy beyond the academy. Anthropology is on display, all the way down. The exhibition is a model for the recovery of the agency of Indigenous people and belongings that were collected by or who worked with ethnographers, and it strives to return the knowledge buried or otherwise silenced by the imbalanced power relations of the ethnographic process. The exhibition will not be truly complete until it goes on display at U’mista, where some of the items shown and reproduced in New York will be displayed in their home context. There, Kwakwaka’wakw communities will be able to evaluate the project’s efforts and provide further comment. Their insights will add to and expand on Hunt’s emendations in a new iteration of the collaborations that sparked a discipline over one hundred and twenty years ago.

Story Box: Franz Boas, George Hunt and the Making of Anthropologyison view at the Bard Graduate Center Gallery from 14 February to 7 July 2019, and at U’mista Cultural Centre from 20 July to 24 October 2019.