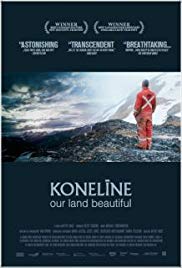

Konelīne: our land beautiful

Review By Matthew Gartner

December 2, 2016

BC Studies no. 195 Autumn 2017 | p. 187-188

Winner of the Best Canadian Feature at the 2016 Hot Docs Festival, Nettie Wild’s Konelīne: our land beautiful weaves together stories of humanity’s relationships with industry, the wilderness, and nature in Northwestern British Columbia. Telling the story of a group of miners who want to work with the locals, as well as Tahltan and other residents who are resistant to the mine’s presence, the film begins with every sign of a text that offers argumentative pushes and empathetic shoves. Ultimately, Wild uses this persuasive mode of documentary to show that some matters are simply too large to be understood through binary formulations. The film makes no judgment between right and wrong, does not give privilege to the enterprise of industry or the conservation of the hinterland, and does not take sides between preservation and progress. In the process, Konelīne opens up the structures on each side of these supposed conflicts, and reveals their own layers of disagreement. While we are tempted to see the residents’ concerns for the land as uniform, the film confuses this by establishing a difference between nature and the wilderness: the former is pregnant with history and value, and the latter can be used to capitalize on this value for monetary gain. With graceful aesthetic touches, Konelīne champions visuals in place of argumentation, and places these atop a nest of interwoven motivations and histories.

Winner of the Best Canadian Feature at the 2016 Hot Docs Festival, Nettie Wild’s Konelīne: our land beautiful weaves together stories of humanity’s relationships with industry, the wilderness, and nature in Northwestern British Columbia. Telling the story of a group of miners who want to work with the locals, as well as Tahltan and other residents who are resistant to the mine’s presence, the film begins with every sign of a text that offers argumentative pushes and empathetic shoves. Ultimately, Wild uses this persuasive mode of documentary to show that some matters are simply too large to be understood through binary formulations. The film makes no judgment between right and wrong, does not give privilege to the enterprise of industry or the conservation of the hinterland, and does not take sides between preservation and progress. In the process, Konelīne opens up the structures on each side of these supposed conflicts, and reveals their own layers of disagreement. While we are tempted to see the residents’ concerns for the land as uniform, the film confuses this by establishing a difference between nature and the wilderness: the former is pregnant with history and value, and the latter can be used to capitalize on this value for monetary gain. With graceful aesthetic touches, Konelīne champions visuals in place of argumentation, and places these atop a nest of interwoven motivations and histories.

The film does begin by emphasizing difference between the miners and those who seek to stop them, and offers a comparatively rich interiority for the latter. When the residents are interviewed or followed, background sounds fill the audio tracks with lively household chatter and music. It is not simply preservation of the natural at stake for these individuals, it is the sustenance of home and culture. In contrast, the miners are offered cold and distant soundscapes, with humming machinery and note-less silence accompanying interview sequences. While a blockade is established to deny the mining company access to a road, the camera remains behind the protectors, leading the audience to see the miners as invaders. At the close of the first sequence that spends time with the mine workers, the camera captures power lines being pulled taut between their supporting towers as the invaders tighten their grip on the region. A shot of gorgeous landscape is interrupted by a worker ascending into the frame as he surveys the land around him.

But as the film moves on, it becomes apparent that these are but two of the many voices that make up a conversation of parallels and conflicts: residents use technology to hunt a diminished population of moose while other residents declare these acts undesirable; some helicopters transfer salmon in order to create sustainable fisheries while others transport electricity towers used to power the mine; individuals oppose the desires of their families and communities by working on the mine; residents industrialize the wilderness and cut down trees in order to create hunting trails; and many established locals still define themselves by frontier imagery and thought.

In place of a conclusive declaration of a victorious perspective, Wild poetically links these stories to sublime shots of the region’s natural beauty. But the camera does not simply capture the skyward carvings of infinite peaks or the diving curves of the valleys. It steps into cartographer’s charts and gorgeous postcards with bird’s eye views of conifers, deep scans of star-filled skies, and vignettes photographed in beautifying slow motion. Konelīne does not ask viewers to measure the success or failure of its exposure of injustice, but rather to reflect on why it is that each character holds their particular view. Common in the motivation of each of the players is their appreciation of the value of the land: sometimes monetary, other times cultural, but always wrapped up in an appreciation of rich, breathtaking imagery.

Editor’s Note: Director Nettie Wild also created an online project, North Through South, in which young urban artists creatively responded to the perspectives of different characters in the film. See https://norththroughsouth.com.

Konelīne: our land beautiful

Nettie Wild

Vancouver: Canada Wild Productions, 2016. 96 mins.