This is Our Life: Haida Material Heritage and Changing Museum Practice

The Force of Family: Repatriation, Kinship, and Memory on Haida Gwaii

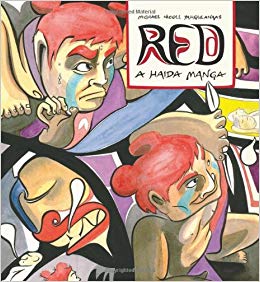

Red: A Haida Manga

Review By Gillian Crowther

March 16, 2018

BC Studies no. 197 Spring 2018 | p. 164-167

All three books included in this review contribute significantly to the body of work concerning the Haida First Nation in British Columbia, with the added importance of bringing Haida voices to the fore in the discussion of repatriation, kinship, and oral traditions, and in the continuity of Haida ways of knowing and doing.

All three books included in this review contribute significantly to the body of work concerning the Haida First Nation in British Columbia, with the added importance of bringing Haida voices to the fore in the discussion of repatriation, kinship, and oral traditions, and in the continuity of Haida ways of knowing and doing.

The repatriation of ancestors’ remains and the material culture held in museums across the globe are issues faced by First Nations in British Columbia and Indigenous peoples elsewhere. First Nations have been instrumental in bringing museums into negotiations concerning repatriation and in finally gaining access to collections. While repatriation is usually situated within the wider political landscape of land claims, treaties, and sovereignty, two books authored or co-authored by Cara Krmpotich of the University of Toronto, This Is Our Life and The Force of Family, return the project to the heart of the Haida community by focusing on the need to be reunited with lost family and property. Both of these books present the Haida motives for repatriation and stand as a testament to the endurance of the Haida through adversity and to the maintenance of the core cultural value of yahgudang, or respect. Read together, these two books are insightful accounts of places and people joined either by the presence or absence of material culture and ancestors’ remains in the museum and the homeland.

This Is Our Life tells of the 2009 encounter between a delegation of 21 Haidas from Old Massett and Skidegate and two museums, the British Museum in London and the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford. The title aptly captures the vitality of all participants, both people and objects, whose professional and personal biographies are woven together by lead authors Krmpotich and Laura Peers of the Pitt Rivers Museum, into a highly readable narrative of the engagement between museums, collections, and source communities. This book offers honest insight into the logistics, dilemmas, anxieties, anger, and joy, which combined for a “bittersweet” experience for museum professionals and the Haida through the six months’ preparations and during the three-week visit. The book’s organization follows a chronological timeline extending from planning, visiting, reflection, outcomes, and on-going future relationships. The ethnographic style of This Is Our Life, with the unobtrusive guiding voices of Krmpotich and Peers, combined with the personal accounts of the museums’ staff and the Haida Repatriation Committee delegates, makes the book an important record of how museums can play a role in the living communities represented in their collections. Towards this end, three central themes are explored: handling, emotional responses, and repatriation, topics that position the book as suitable for use in museum, material culture, and First Nations studies.

The first theme, the handling of objects and the need to balance physical wear and tear with the value of experientially produced knowledge, reverberates through all the chapters of This Is Our Life. The Haida delegates’ accounts of their need to touch objects are particularly moving and demonstrate the power of the Haida concept of yahgudangang, or mutual respect, which appeared to soften the curatorial resolve to limit handling. Relationships between Haidas and museum staff were based, in turn, upon the relationship each group had with the collections of objects, which illustrates the second theme of sensorially triggered emotions. Through engaging with one another, and with the objects, these accounts explore the acquisition of knowledge — artefactual and ancestral — and articulate the unleashed emotions, such as anxiety provoked by a loss of control for conservators, and the joy, or grief, of reconnection with ancestral Haida.

The third theme of repatriation strikes at the heart of the encounter between the collectors and the collected. The Haida readily acknowledge their desire to have ancestral remains repatriated for burial to Haida Gwaii, and for objects — not all, but some — to return to their home communities. In turn, the museum-based authors honestly address the discomfort felt by UK museums about repatriation, whilst presenting the Haida Project as an important institutional step to involve “source communities” in collections management, research, and display. Thus, the book speaks to the changes museums have undertaken spurred on by the protests of formerly colonized Indigenous peoples in Australia, Canada, and the United States. This Is Our Life and the Haida Project are primarily concerned with access to collections that foster the repatriation of knowledge, not the objects themselves. Cultural knowledge is acquired by the museums to add to their databases, to facilitating accurate and sensitive care and display of the collections, while the Haida repatriate the fragmented knowledge of their “hidden culture” (188) to inspire and strengthen the living Haida culture at home on Haida Gwaii. This exchange, and generation of new knowledge and understandings, emerges from understanding the British Museum and the Pitt Rivers Museum as “contact zones:” places where new, collaborative understandings could be reached.

The last two chapters of This Is Our Life explore the importance of maintaining the relationships born from the Haida Project, such as the return of an ancestor’s remains from the Pitt Rivers Museum. Akin to a rite of passage, all involved — the Haida delegation and the staff who met them — are changed by the emotional intensity of the experience and, in keeping with the sentiments of kinship, embrace mutually respectful cooperation. While providing an optimistic vision of how museums can become postcolonial institutions, it is tempered by a final realistic assessment of the challenges that remain, such as accommodating Indigenous classifications within museum databases, championing access and handling over preservation, and the funding of repatriation.

The Force of Family: Repatriation, Kinship, and Memory on Haida Gwaii, Krmpotich’s account of her 2005-2006 fieldwork on Haida Gwaii, which shaped the subsequent 2009 Haida Project, focuses upon repatriation from the perspective of Haida motivations. Through interviews and experiences, she reveals repatriation as an outcome of the enduring ties of kinship, the responsibilities of the living towards their ancestors, and their need to return home ancestors’ remains and material culture to strengthen the community. This sensitively written and insightful ethnography takes repatriation away from the control of museums and places it in a specific community as it tries to repair the damage of over a century of social and cultural trauma. The Force of Family provides a synopsis of the history of contact, of changing relationships with museums and, more importantly, concentrates upon Haida responses to reconcile the past with the present and to draw continuity through colonial rupture.

In their interviews with Krmpotich, Haidas drew attention to reincarnation as a means to strengthen and calm the contemporary community. They believed that the return of over 400 ancestors’ would continue this genealogically and spiritually significant process. The connections between kinship, material culture, and memory are so well developed in The Force of Family that this accessible ethnography must be considered as a text for social anthropology courses. Kinship and yahgudang are clearly explained by Krmpotich and by the Haidas whose voices are present throughout the book. It is this strength of family through time and place and the cultural value of doing what is right — of acting in a respectful manner towards oneself, towards kin, to one’s matrilineage, and to the interdependent lineages of the moiety structure — that underscore the necessity to return displaced ancestors to their homeland. Krmpotich charts the Haida Repatriation Committee’s exhaustive efforts and the desire of the Haida community to return, welcome, mourn, and ceremonially inter their ancestors. She brings home that this is the Haida way: a returning to normal.

One of the Haida Repatriation delegates, Jaalen Edenshaw, reflecting upon a bentwood box by his ancestor Charles Edenshaw, noted the master Haida artist had not been “bound by many of the modern conventions” (171) that have become standard in Haida art, a comment that also captures the work of Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas’s Red: A Haida Manga. This sumptuous graphic work, derived from Haida art and Japanese manga, captures the flexible telling of a Haida oral tradition and offers opportunities for many interpretations. Red will appeal to anyone interested in graphic novels, Japanese manga, First Nations art and oral traditions, and in a good story told and visualized so effectively.

Not a quick read, Red is worthy of lingering, tracing with fingertips, and flicking backwards and forwards as the story unfolds. Filled with loss and tragedy, the story concerns the orphan Red, the abduction of his sister, and his desire for revenge. The telling of this cautionary tale is full of beauty, colours, and flowing black formlines that lead the viewer through interlinked scenes packed with vitality. Yahgulanaas gives permission to destroy the book and reassemble it with another copy as a panel to reveal the flow of the narrative and the depth of the graphic asides: glimpses of domestic life, fishing, forests, animal species, art, and material culture. In a manner that bridges the past and the present, Red brings alive the world of the Haida ancestors whose remains are now being repatriated.

This is a contemporary telling of a traditional story with an abiding message of the negative consequences of fear, anger, and revenge. Red’s desire to be reunited with his sister, his kin, resonates with the Haida motivations behind the repatriation of abducted ancestors’ remains in This is Our Life and The Force of Family. Unlike Red, the Haida Repatriation Committee, upholding yahgudangang, does not succumb to emotions easily born from the legacy of colonialism. With any good story it will continue to be relevant with every telling, and Red: A Haida Manga’s visual, emotional, and intellectual appeal will ensure it is read and re-read.

Publication Information

This is Our Life: Haida Material Heritage and Changing Museum Practice

Cara Krmpotich and Laura Peers, with the Haida Repatriation Committee and staff of the Pitt Rivers Museum and British Museum

Vancouver: UBC Press, 2013

The Force of Family: Repatriation, Kinship, and Memory on Haida Gwaii

Cara Krmpotich

Toronto: Toronto University Press, 2014

Red: A Haida Manga

Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas

Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 2014