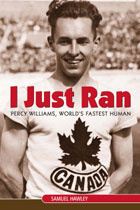

I Just Ran: Percy Williams, World’s Fastest Human

Review By Russell Field

November 4, 2013

BC Studies no. 176 Winter 2012-2013 | p. 176-7

A feature attraction at the 2012 London Olympics will be Jamaican Usain Bolt’s attempt to repeat his feat from four years ago in Beijing of winning gold medals in both the men’s 100m and 200m sprints. Canadians might be forgiven if they’ve forgotten that 80 years ago, the Los Angeles Olympic 100m sprints featured the final race of Vancouver’s Percy Williams, who like Bolt was trying to repeat Olympic sprint success. Celebrated at the time as the “world’s fastest human,” four years earlier Williams had shocked the sporting community by winning both the 100m and 200m races at the 1928 Amsterdam Games. Before his career was cut short following a leg injury suffered in 1930 while winning the 100m gold medal at the first ever British Empire (now Commonwealth) Games, Williams would retire from competitive racing as the 100m world record holder (10.3 seconds).

Williams’ unexpected rise to sports stardom and the status of national hero is the subject of I Just Ran, a new biography by Kingston, Ontario-based writer, Samuel Hawley. Williams’ slight stature, his recovery from a teenage bout with rheumatic fever, and his sudden emergence as a world-class sprinter while still a Vancouver high-school student working with Bob Granger, a part-time coach and school custodian, are the ingredients of the familiar underdog-makes-good narrative. However, if Williams was, in the aftermath of his unexpected victories in Amsterdam, “the flesh-and-blood representation of how the country viewed itself and what it wanted to be” (4), his fame came with few monetary rewards and, as Hawley chronicles, Williams was as eager to leave behind the strictures of nineteenth century amateur sport for a career in business as he was to continue running in international meets.

Throughout I Just Ran Williams comes across as a reticent public figure, weary at having his every move chronicled and reluctant to reveal his private thoughts for public consumption. Hawley consults the runner’s diaries to make this private figure public, but these often reinforce the sense that Williams wanted his life unexamined (and in his exasperation, the young sprinter also reveals moments of cultural insensitivity). To fully sketch out the context of his character, Hawley makes extensive use of contemporary newspaper coverage. As a result, Williams the athlete in the public eye is very much the focus of this biography and considerably less attention is paid to his private life, post-sport career, and eventual suicide. Newspapers are also not entirely unproblematic sources. As Bruce Kidd details in his examination in the Canadian Journal of History of Sport (14, 1 [1983]) of the press coverage of the Onondaga First Nations long distance runner, Tom Longboat, the early twentieth century sport press constructed narratives of public figures which often reinforced classed, gendered, and racialized stereotypes. The discourse surrounding Percy Williams, the national hero and amateur exemplar, reflected this process.

Hawley uses Williams’ competitive career to shine a light on the life of the early twentieth century amateur athlete, which was framed in altruistic terms in contemporary accounts, with sport pursued by men (amateurism in its earliest incarnation was almost exclusively for men) just as interested in the values of healthy competition, fair play, and sportsmanship as in winning. Indeed, Vancouver reporter Robert Elston wrote that “Percy Williams retains something of a classic amateurism in spite of all temptations” (236). Williams, however, was not immune to the financial temptations that lurked beneath the surface of amateur competition. Hawley details that even in the late 1920s, track athletes were receiving under the table payments from promoters eager to enhance ticket sales at their meets by attracting high-profile competitors with “discreetly passed envelopes … typically containing just a few hundred dollars” (167). The rules of amateurism and the harsh penalties for disregarding them were administered from Toronto by the Amateur Athletic Union, and East-West tension pervades Williams’ running career. For Vancouver’s civic leaders and newspapermen, Williams might have been a national sport hero but for their purposes he represented the Terminal City. He was BC’s sprint champion “standing up to the arrogant East” (4).

I Just Ran: Percy Williams, World’s Fastest Human

By Samuel Hawley

Vancouver: Ronsdale Press, 2011. 260 pp. $23.95